People disillusioned with religion say there is no such thing as a religious morality. They claim there is only a set of texts from which you can extract anything and justify whatever you need. Take Judaism, for example: the famous commandment “You shall not kill.” Does Judaism say you cannot kill? No — it simply specifies whom to kill, when and how. For instance, the descendants of Amalek, including infants; or a Jew who does not keep the Sabbath; or a woman who betrayed her husband. “Jewish values” and the norms of Judaism are used to justify virtually every position — from Jewish nationalists who destroy Arab villages in the West Bank to organizations calling for a single state of Jews and Arabs. It is striking that some Orthodox Jews do not recognize the State of Israel at all. The same situation exists with Christianity and Islam. Defenders of religion say: “We have a dogma revealed from above.” So why are these dogmas so strangely contradictory? If this is divine doctrine — what makes religious morality preferable to others — how can people interpret it so heterogeneously, edit it, or add to it? Shouldn’t it be perfect from the start?

The answer is that revelation is possible only within the moral and conceptual horizon of a society. If it radically exceeded that horizon, people could not recognize it, interpret it, or accept it — it simply would not be heard. Revelation (religious morality) cannot be absolute truth in the abstract; it must be a translation of truth into the language of its time. Revelation cannot be given to a society as if it were a university course handed to an infant. It must be proportionate to the moral and spiritual development of its listeners, otherwise it remains meaningless noise. Divine revelation remains true, but the form in which it is conveyed inevitably takes into account the moral and cultural level of its recipients. Therefore God speaks not outside of history but within it — expanding human moral consciousness step by step.

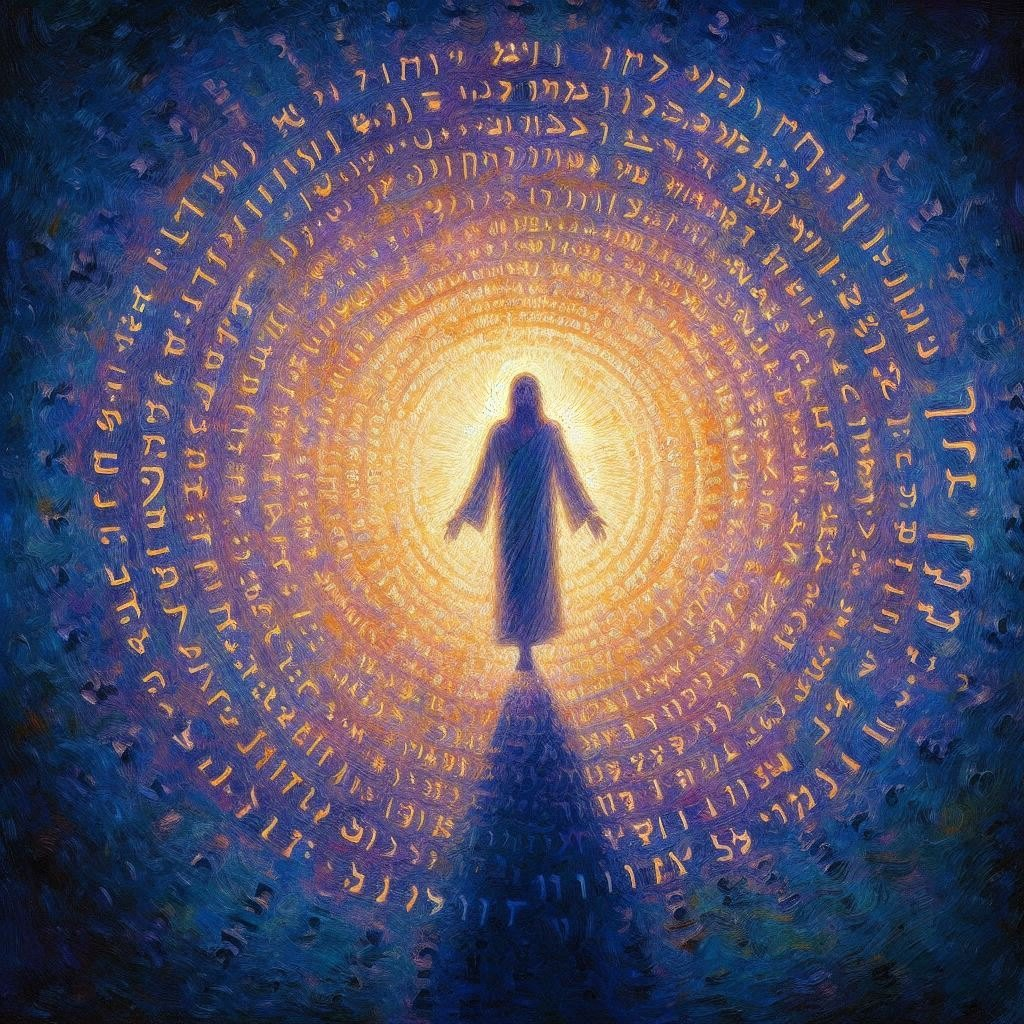

A perfectly natural move, then, was to show humanity a perfect human being, rather than hand down yet another manuscript of prescriptions. Jesus Christ, the perfect man, lived among the people of his time, accessible and understandable; he demonstrated absolutely ideal religious morality in both word and deed. All the witnesses who recorded and reflected on Jesus’ person constituted the real social horizon within which a moral improvement took place.

Let us compare the person of Jesus, his teaching and actions, with the Ten Commandments of the Old Testament. Jesus does not abolish the Decalogue, nor does he confront it head on, but he shifts the focus from external observance to the inner state of the person. Jesus declared: “Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish but to fulfill.” The word “fulfill” (Greek: πληρόω) means to bring to fullness, to reveal the authentic meaning, not merely to carry out something formally. The Ten Commandments are mostly framed as external behavioral norms — do not kill, do not commit adultery, do not steal, do not bear false witness. Jesus takes the next step: “You have heard that it was said to those of old… But I say to you…” The point is that sin does not begin with an act but with an inner rupture. He asserts that these commandments are not legal norms but existential conditions. Not simply “do not kill,” but be reconciled. Not simply “do not steal,” but share with those in need. Not simply “do not lie,” but be truth. Not simply “do not take revenge,” but forgive. It is a shift from minimal moral adequacy to active love.

The new criterion is not the law but the Person. The center is no longer the commandment but Jesus himself, who said: “I am the way, the truth, and the life.” The standard is no longer whether my action conforms to a rule but whether it conforms to the image of Christ. The Ten Commandments became the minimal moral framework of society, while Jesus’ teaching is the path of inner transformation. Jesus’ teaching does not stand beside the Ten Commandments; it does not negate them. It stands above them — meaning over letter, life over rule, personality over norm.

One question remains: why did Jesus so radically revise the fourth commandment about the Sabbath? Jesus healed on the Sabbath, allowed his disciples to pluck grain, and ignored Pharisaic hair-splitting about “what counts as work.” This was not an accident but a consistent position. In Jesus’ teaching the Sabbath ceased to be an absolute value; it became an instrument, not an end in itself. Jesus did not abolish the commandment “do not kill,” but he deepened it. He did roughly the same with the other commandments, but he made the Sabbath relative because it was not the core of morality. This revision means that not all commandments have equal status: the moral is above the ritual, love is still higher than the discipline of the seventh day, even though keeping that day in rest is good. The Sabbath was a marker of “us versus them”; it easily became a loyalty test for the system and simply encouraged religious discipline. Jesus clearly affirmed that the issue was not merely discipline: there are values higher than discipline.

Jesus explicitly reduces the Law to two principles: “You shall love the Lord your God… and you shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments hang all the Law and the Prophets.” Why did this thesis provoke conflict? Because Jesus really cut away the unnecessary, and for Jews this was very painful. Jesus broke Sabbath prohibitions, associated with “sinners,” touched the sick and ritually unclean, elevated love above ritual, denied the temple as the absolute center of religious life, and declared that food does not defile a person. The old code of religious life was revised by the life of Jesus. Jesus recognized under “the Law and the Prophets” only what pertained to the high divine truths and rejected the secondary elements in the Old Testament that had been produced by human beings.

Thus Jesus did not leave behind a new code of rules — he himself became the measure and source of religious morality. The Law ceased to be a text demanding endless interpretation and became an embodied reality open to imitation. In him morality is no longer fixed in prescriptions but manifests itself in a living relation to God and to other people. Jesus does not appear as another lawgiver but as a catalyst of moral consciousness, translating religion from a mode of compliance into a mode of life. Where people once asked, “What is permitted?” a different question now arises — “How would Christ act?” In this sense Christianity is founded not on a code but on a Person, and that is why it can renew morality without rewriting it from scratch.

Leave a comment